With the province seeing 596 deaths due to the toxic drug crisis from January to the end of March, 2023 is only three deaths short of the record breaking year in 2022, which had 599 fatalities over the first three months. Since 2016, when the provincial public health emergency was declared, more than 11,000 lives have been lost.

Drugs across the province have grown increasingly toxic, leaving Nuu-chah-nulth friends, family, and the broader communities grieving the loss of their loved ones.

Of the 11,000 lives lost throughout the province, one thousand are First Nations, said Nel Wieman, originally from Little Grand Rapids First Nation and First Nations Health Authority (FNHA) acting chief medical officer, at event for the release of 2022 Toxic Drug Data for B.C. First Nations people.

“Toxic drugs have impacted all of our families and all of our communities and left our people devastated,” said FNHA Board Chair Colleen Erickson, who is from Nak’azdli. “My personal experience is that we are losing a whole generation of young people.”

In 2022, 373 First Nation lives were lost to the toxic drug crisis, making a 6.3 per cent increase from 351 deaths in 2021.

“There is a disproportionate impact on First Nations people in this province, although we represent only 3.3 per cent of the province's population,” said Wieman. “In 2022, we represented 16.4 per cent of toxic drug poisoning deaths. In 2021 this was 15.2 per cent.”

In 2022, 36.5 per cent of First Nation deaths were women, with a death rate of 11.2 times higher than other women residing in B.C.

“The overall trend is that First Nations people are disproportionately dying from B.C.’s toxic drug crisis and the gap continues to widen,” said Wieman.

Root causes of the toxic drug crisis among First Nation people are connected to intergenerational and ongoing trauma from colonial impacts of residential schools, the sixties scoop, and discovery of unmarked graves, said Wieman.

“[FNHA] recognize that the toxic drug public health emergency is a very visible manifestation of long-standing health inequities, including intergenerational and contemporary trauma, culturally unsafe care, unmet needs, and a disjointed mental health system,” said Katie Hughes, vice-president and public health response for FNHA.

The FNHA data shows that some First Nations people struggle with opioid-use disorder, while others have medical conditions that are undertreated. Some are experimenting, and others use intermittently, explained Wieman.

Richard Jock, Mohawk of Akwesasne and CEO for FNHA, notes the significant lifestyle and communication changes that occurred due to the pandemic impacted the mental health crisis.

“These changes and these different realities and degrees of isolation, have really had their impact,” said Jock. “As we were going through COVID-19, we did acknowledge that mental health would likely be the next challenge directly coming from this. I would say that, at that point, we certainly didn't anticipate the level of effects from toxic drugs that we're seeing today.”

“The emergency can only be met by [a] head on response,” continued Jock. “It is now our top priority within the First Nations Health Authority. As part of that we've moved to level two response.”

For FNHA a level-two response means the implementation of a public health team to be the “chief mechanism” in expanding resources to meet the ever-changing needs of the opioid crisis, said Jock.

Strategies include building on Indigenous people’s resilience, addressing root causes, and providing holistic healing to support First Nations throughout the province, said Hughes.

Among the many efforts addressed by the FNHA, Hughes highlighted treatment centers shifting to a healing and wellness-centered model and expanding to underserved regions.

“A range of options are needed to truly meet people where they're at in their healing journeys and to support self determination,” said Hughes.

Moving forward, Hugh said that efforts will be directed at securing funding, expanding their virtual substance use and psychiatry service, investing in a First Nation-led overdose prevention and mobile harm reduction services, expanding community capacity and harm reduction services, among others.

Hugh also said that FNHA is working with the province and local health authorities to increase the number of detox and treatment beds for First Nation people.

FNHA is supporting First Nation women with harm reduction measures, such as overdose prevention sites, in communities like the Downtown Eastside, added Wieman.

Dr. Shane Longman, a physician in Port Alberni, administers medications used for Opioid Agonist Therapy (OAT), which uses methadone and suboxone to treat withdrawal symptoms so that individuals can transition away from using.

“The philosophy of care has to change in the community, in the healthcare system, in physicians offices, in the hospital, in [emergency]; everywhere,” said Longman. “The other thing that needs to happen is that access points to care need to be increased.”

“Access points mean not only the physical locations, but also timing… when individuals need it, it needs to be available for them,” he continued.

Longman uses the example that he now goes to police cells to administer OAT medications to help people with their withdrawal symptoms.

“Sometimes that translates into individuals that then stay on the medication and do very well,” said Longman.

“The toxic drug crisis is not just a Downtown Eastside problem, there are people dying, including First Nations people, in every corner of this province,” said Wieman when asked about how to fill the gap in services for remote and rural First Nation communities. “When we talk…at a provincial level about what types of interventions would be most helpful, we're really forgetting the realities of First Nations people who live in very rural, remote and isolated communities.”

For significant changes in preventing the deaths among First Nations, the focus needs to shift from larger to smaller regions in a way that is feasible, sustainable, and effective, she continued.

Wieman notes that a lack of front-line workers in remote communities and burnout can be a barrier to implementing services.

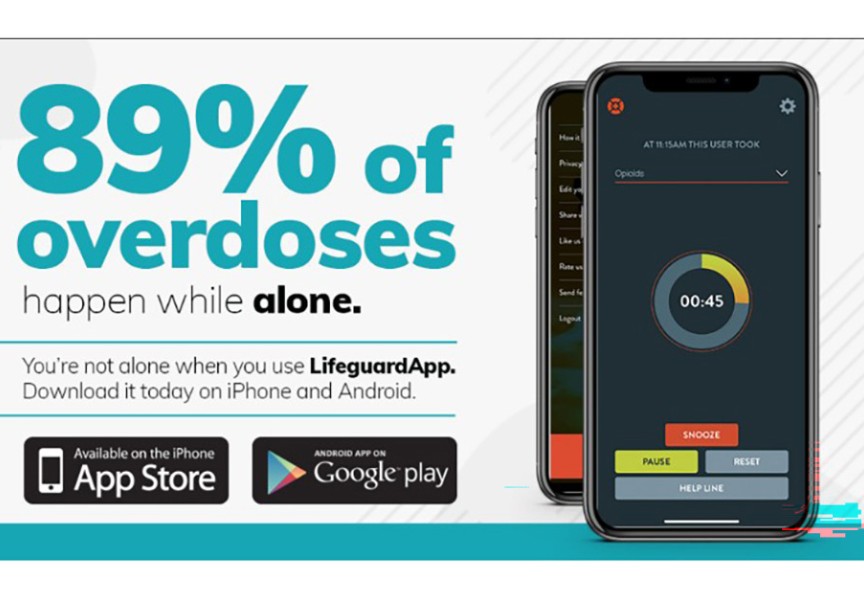

FNHA currently offers a virtual substance use and psychiatry service that provides referral-based culturally safe support. For those unable to access professional support, the First Nations Virtual Doctor of the Day can provide referrals to this service.

“2022 was the most devastating year for First Nations people, their families, friends and communities in terms of the toxic drug crisis so far,” said Wieman. “We need to build hope that we can turn things around [and] prevent more deaths.”

“These numbers are people; people who loved and were loved,” she added.