It was on Aug. 31, 1973 when the Alberni Indian Residential School (AIRS), on Tseshaht’s main reserve, closed its doors for good.

Charlie Thompson, a survivor of AIRS, recalls when the West Coast District Council of Indian Chiefs began to discuss the closure of the school in 1972. Thompson was working as a band manager for Ditidaht and attended meetings with his father, Webster Thompson, who was the First Nation’s elected chief councillor at that time.

“The discussions around shutting it down was music to my ears,” said Thompson, who had two children who were getting to the age when they would have gone to the school.

Taking the reins on education

Thompson said that the publication of a paper by the National Indian Brotherhood, now known as the Assembly of First Nations, called, “Indian Control of Indian Education”, was what started the conversation of the AIRS closure.

Because of this paper, said Thompson, chiefs across Canada began to talk about how to take on the responsibility of educating their children.

According to a report by the Canadian Senate in 2011, the publication was to counter the White Paper, also known as the Statement of the Government of Canada on Indian Policy of 1969. The White Paper proposed that the education of First Nations children be the responsibility of the provincial government.

“The chiefs of the West Coast District Council got together and they started talking about what that's going to look like, [and] what we could do as leaders of our communities to take over the education of our children,” said Thompson. “The obvious blockage was Indian residential schools.”

Thompson said that throughout discussions of the West Coast District Council there was no doubt in their minds that they had to take on the responsibility of their children's education.

He also noted that briefly, the West Coast District Council discussed taking over the running of the school, which was ultimately rejected.

The historic meeting that closed AIRS

George Watts, Simon Lucas, and Nelson Keitlah were tasked with negotiating with the Department of Indian Affairs in Vancouver, said Thompson.

According to a press release from Tseshaht First Nation, a letter was sent from the West Coast District Council to the Department of Indian Affairs on July 3, 1973 which proposed the closure of the school. This letter, signed by George Watts, led to a meeting in Vancouver.

Ken Watts, current elected chief councilor of Tseshaht, sees this meeting as one of the “historic” events that the West Coast District Council did in their early years.

Watts, son of late-George Watts, shared that when they went to Vancouver, the regional director said, “What do you want George? What can I do for you?”.

“My dad said, ‘We want the residential school closed’, and my dad said, ‘Tomorrow’,” shared Watts.

“It's one of those things that ended something; ended something pretty substantial, and it should never be forgotten,” said Watts.

“They came back to the tribal council meeting and said, ‘Okay, we're on course to shut this place down, it's going to shut down, we've got the big shot in Vancouver on [our] side,” said Thompson.

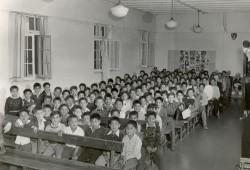

According to The Children Remembered, until 1920 the school’s main attendance were children of Tseshaht and Hupačasath. By the 1940s enrollment grew from the Vancouver Island region to students from First Nations throughout the province.

Lucas and Keitlah were then tasked, by the chiefs, to go to each home village of the students in attendance at the school to inform their parents of the plans for the coming year, said Thompson.

Opposition and moving forward

Thompson shared that when the chiefs brought up the closure of AIRS and Christie Residential School from the West Coast District Council to their communities, they were met with some opposition, though the majority agreed.

Thompson believes that people thought, “Our kids are going to get educated, it’s a good thing to know the white man's ways”.

“But in the end, that really didn’t happen,” he said. “Some went as far as to graduate, but that was rare. Most of us never finished school.”

Thompson also said that families faced the threats of fines and imprisonment.

“Our grandparents were scared,” said Thompson. “I think they gave into the government by sending their kids to the schools.”

For Ditidaht, when the school closed, they built a small school on their home reserve for children up to Grade 6, said Thompson. The older children were then bussed each day to Port Alberni; the band soon took over transportation from the school district after buying a school bus.

“Other people started doing the same thing,” said Thompson.

Former school buildings, reclaiming a place to heal

Over the decades since AIRS closed some of the former buildings had been demolished, though two of those structures remain; one is utilized by the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council, formerly known as Caldwell Hall, and the other is Maht Mah’s gymnasium where community events and meetings are held.

In 2007, over thirty years after the closure of AIRS, Tseshaht’s administration office moved from Peake Hall, a former AIRS dormitory, to their new building located along the Somass River, according to a Ha-Shilth-Sa article.

Later, a ceremonial demolition of Peake Hall was held for survivors as the building was torn down, with smudging and blanketing done in Tseshaht’s longhouse.

“Imagine how difficult it was for some of our members to have to enter that building to work or for support services,” said Les Sam, Tseshaht’s former elected chief councilor, in a 2007 issue of Ha-Shilth-Sa. “When the worst experiences of their lives, when they were just children, happened in that very building.”

The Hall was replaced with a basketball court, said Watts. He reflected on survivors who spoke about “how great it was to see kids happy there, [in] a place that wasn’t so happy for them.”

For Tseshaht, the closure of AIRS and the work of continuing to reclaim where the school stood is “helping create a safer space in our community,” shared Watts.

“It’s helping people’s willingness to come back because those buildings represent a dark history,” he said. “It’s an open wound for many who aren’t willing to cross the bridge.”

“That’s why we painted ‘Every Child Matters’ on the bridge,” Watts added.

Watts shared that for years he has been working with Canada to tear down Caldwell Hall, and they have made a commitment in writing.

“Our hope is that when we remove those [buildings] it’ll help create a new history there,” said Watts. “Reclaiming the space as ours because it's our territory.”

Following phase one of Tseshaht’s LiDar scanning and investigation, where they found at least 67 children died at the school, Tseshaht announced 26 Calls for Truth and Justice. One of these calls is under Canada’s Residential School Infrastructure Fund.

Included in this call is for Canada to fund the deconstruction of Caldwell Hall and an event, as well as supporting the construction of a community center with facilities in former AIRS buildings, such as a gymnasium, fitness gym, commercial kitchen, and office spaces. The call also mentions funding the deconstruction of the gymnasium if Tseshaht chooses to do so, reads the statement.

Watts said that in the coming months the Tseshaht community will be gathering to decide how they would like to move forward with the gymnasium, known as Maht Mah’s.

“I sure realize how important our people gathering here, on our territory, in a place where we have such an open wound, is important to all Nuu-chah-nulth and all survivors,” said Watts. “That building needs to be… a place of healing, not just for meetings or cultural events, but for sports, for simple gathering.”

Only fifty years ago

“To me 50 years… doesn’t seem a long time ago,” said Thompson. “In the end it’s a blessing because of the hard work of those people who made it happen.”

Thompson shared that he is thankful for the chiefs of the West Coast District Council who in 1972, decided to take on the responsibility of their children’s education and close the school.

“They did the right thing to close it down rather than continue to allow Indian Affairs to run our lives as kids,” said Thompson, reflecting on the hard work to close the residential school. “I have a small part in it, makes me feel great.”

“We didn't ask for it, but we have to live with it,” said Watts. “And now we have to try to help fix those wrongs made by others so that we can create a better community for everybody.”