It has been just over a year since the province enacted an exemption under section 56(1) of the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act to decriminalize people who use drugs.

The federal government approved an exemption to allow for the removal of criminal penalties for possession of small amounts of some illicit substances for personal use by people over 18 years old within British Columbia. The decriminalization ‘experiment’ came into effect Jan. 31, 2023, and remains in effect until Jan. 31, 2026.

The rationale behind decriminalization of some drugs for personal use is to treat drug use and dependence as a health and social issue, not a criminal justice or moral matter. British Columbia is the first province in Canada to decriminalize small amounts of drugs.

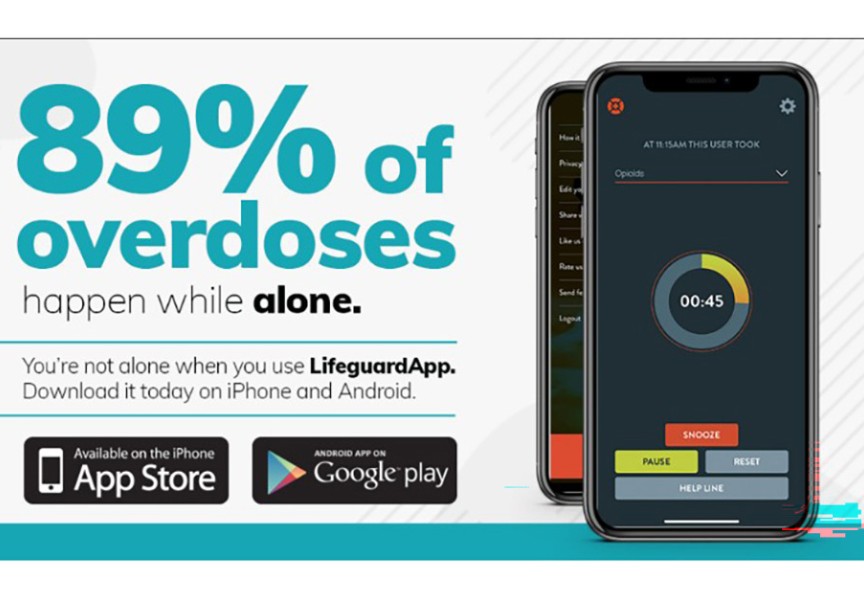

Those that support decriminalization have argued that law enforcement activities may compel people to use alone, thereby increasing the risk of death from overdose.

A staunch supporter of decriminalization, in November 2021 Gord Johns, NDP Critic for Mental Health and Addictions said, “Decriminalizing personal possession of drugs in the province and across Canada is an essential first step to removing the shame that often prevents people from reaching out for life-saving help. Addictions is a disease, not a crime.”

But since the start of decriminalization, drug use has become more visible as people are openly using in public spaces and since there is nothing illegal going on, the hands of law enforcement officers are tied.

On April 21 the provincial government announced that it is taking action to ban illicit drug use in public spaces.

“In November 2023, the B.C. government passed the Restricting Public Consumption of Illegal Substances Act (RPCISA),” said the Office of the Premier in a written statement. “The intention of the act was to provide law enforcement with more tools to address instances of inappropriate drug use in a variety of public places such as parks, beaches, sports fields and community recreation areas, as well as near business and residential building entrances and bus stops. This legislation is currently being challenged in court.”

The province says it is working with Health Canada “to urgently change the decriminalization policy to stop drug use in public” and is asking for an amendment to the s.56 policy to exclude all public places except spots like private residences and health care clinics that provide outpatient addictions services.

“Keeping people safe is our highest priority,” said Premier David Eby in a statement issued April 26. “While we are caring and compassionate for those struggling with addiction, we do not accept street disorder that makes communities feel unsafe.”

Under the proposed new changes, law enforcement will have the ability respond to a scene where drug use is taking place and will have the ability to compel the person to leave the area, seize drugs when necessary or arrest the person, if required.

In addition to making illicit drug use illegal in public spaces, the province vows to expand access to treatment for those in addiction.

According to information from the provincial government, there have been 600 publicly funded substance-use treatment beds opened in the province since 2017. There are 50 overdose prevention sites in B.C. and, since 2019, the province has spent $35 million to support 49 community counselling agencies.

Another move the province is going ahead with is providing additional security at hospitals to deal with unacceptable behavior such as aggression, noncompliance with policy, drug dealing, harmful exposure of illicit drug residue and smoke to hospital staff.

The provincial NDP government has been under fire from the opposition BC United Caucus (formerly BC Liberals) who say the policy has caused chaos and harm.

Todd Stone, BC United House Leader, pressed for a debate and a vote on the BC United motion for the full repeal of “David Eby’s reckless and failed decriminalization experiment.” But the motion was voted down.

The BC United Party offers up their ‘Better is Possible’ plan which they say prioritizes treatment, recovery, and rigorous enforcement against drug trafficking to safeguard B.C. communities. With an election approaching this fall, they vow to end the “NDP’s disastrous decriminalization policy and taxpayer-funded drug diversion.”

They say a Kevin Falcon-led government would pursue the elimination of user fees for treatment, build five regional recovery centers in the province and increase access to a virtual opioid dependency program so that those without access to physicians can get immediate treatment.

Their plan includes ideas on how they would address homelessness as well as promote addiction awareness and prevention programs for a combined price tag of $1.52 billion over three years.

According to the B.C. Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions, the NDP announced it would build on the previous year’s $1 billion budget for mental health and addiction supports to $2.6 billion, expanding the Redfish Healing and Road to Recovery models.

According to the BC Coroner’s Service, there has only been one recorded accidental overdose death in a supervised prevention site and that there is no indication that a prescribed safer supply is contributing to unregulated drug deaths.

The B.C. government and public health officer declared a health emergency in April 2016. Since that time more than 14,000 British Columbians have died of accidental opioid overdoses.