The Nuchatlaht have filed with the B.C. Court of Appeal, launching the next phase of its legal battle to gain title over the northern part of Nootka Island.

The appeal was announced Sept. 16, seven and a half years after the small First Nation’s late Tyee Ha’wilth Walter Michael stood on the steps of the B.C. Supreme Court to begin his community’s claim to own what they have considered their home territory for countless generations.

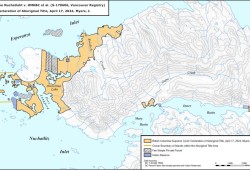

The appeal challenges the extent of a decision from Justice Elliot Myers, who determined in May 2023 that the Nuchatlaht are the rightful owners of portions of the area – but not all of the 201 square kilometres that the First Nation claim Aboriginal title to. This judgment followed over 50 days in court that began in March 2022, a trial in which the First Nation’s legal team and the provincial government presented evidence concerning the Nuchatlaht’s rightful ownership of the territory. This all hinged on the legal test of proving a historical and continued occupation of the claim area since 1846, the year that the British Crown asserted sovereignty over the land.

“We have been fighting for our rights since my great grandfather told the Indian agent to stop giving away our land over 100 years ago,” stated current Tyee Ha’wilth Jordan Michael in a press release from the First Nation. “We have been determined for over a century. This is only a partial victory. We are not going to stop now.”

In March of this year Myers allowed the Nuchatlaht and the province back to court to argue the exact extent of the Aboriginal title claim. This resulted in an April 17 decision in which the judge defined the title to a small portion of the total claim, mainly consisting of a coastal strip along the west that doesn’t extend more than one kilometre inland.

A major part of the Nuchatlaht’s evidence presented in court was the many trees that were partially harvested by the First Nation’s ancestors. This included the 8,386 culturally modified trees identified by archaeologist Jacob Earnshaw, but in his judgment Myers noted that these CMTs were an average distance of 845 metres from the shore.

“With respect to the interior, there is almost no evidence of use by the Nuchatlaht,” wrote Myers, who was unconvinced that the nation’s ancestors left evidence of occupation above an elevation of 100 metres. “Confining the boundary to the 100-metre contour reflects the distinction between the coastal and interior areas.”

At the time the Nuchatlaht celebrated this decision as a victory, marking only the second time a Canadian court has granted a First Nation Aboriginal title. A decade ago the Supreme Court of Canada recognized the Tsilhqot’in Nation, a historically “semi-nomadic” Indigenous community, for its demonstration of being the rightful owners of large area in central British Columbia.

But the April 17 ruling also made it clear that court proceedings for the Nuchatlaht were far from over, as Myers’ decision leaves most of its traditional territory as Crown land currently under a Western Forest Products’ forestry tenure. Forestry operations in the claim area have ceased as court proceedings progressed.

From the beginning of the First Nation’s legal proceedings management of Nootka Island’s resources have been a foremost concern, as large sections of the claim area are scalped by clearcuts, practices that pose a risk to salmon streams that were historically owned by chiefs.

“We are a small First Nation, but we will not be bullied by the province because we forced them to answer us in court,” stated Nuchatlaht Councillor Archie Little. “Our territory used to sustain us, but it has been mismanaged. Our fish and our forests are hurting. We want to handle things differently, so that there is a path forward for everyone.”

The First Nation also noted “significant hurdles” in its court battle with the province, including having no surviving fluent speakers of the Nuu-chah-nulth language and that key evidence in the claim area has been destroyed by logging.

Nuchatlaht Councillor Melissa Jack stressed that her nation’s use of its territory went far beyond the village sites that were at the mouth of a river.

“Our territory didn’t stop at the village limits or the bottom of the hill,” she stated. “Our people used everything from the clams on the beaches to the yellow cedar on the mountain tops.”

“The mountains that guided our boats home over 100 years ago haven’t changed,” added Councillor Erick Michael. “We knew what was ours then and we know our territory today.”

For the First Nation of less than 160 members, part of its path forward could be looking north to a recent development in Haida Gwaii. In April the province and the Council of the Haida Nation finalised an agreement that acknowledges the Indigenous community’s title over all of Haida Gwaii - marking a glaring contrast to the stance that the government has taken against the Nuchatlaht in court, argues the First Nation.

“While passing legislation acknowledging Haida Aboriginal title to all Haida Gwaii, the province spent the Nuchatlaht trial claiming the mountains are too remote and the forests too thick for the Nuchatlaht to have ownership,” stated the First Nation in its press release.