Sweetness is the $1 million milestone Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks crossed this year in ecosystem stewardship contributions from Tribal Parks Allies businesses.

Since launching the program in November 2018 with four Allies and $15,000 in donations, the number of participating businesses has increased to 127. In the 2023-2024 fiscal year those partners contributed a combined total of $444,318 to support Tribal Parks coastal restoration initiatives, salmon enhancement, trail building, community outreach and more.

Sweeter still, the late Nancy Powis, a passionate member of the Tofino community, bequeathed 50 per cent of her estate to Tribal Parks, amounting to $1.2 million. The magnanimous gift was put into an endowment fund and a garden with a commemorative bench will be erected along the Big Tree Trail on Meares Island, Tla-o-qui-aht’s flagship hike with some of the world’s oldest cedars.

“I’m proud of where we’ve come and where we’re going. It’s been a busy summer,” said Saya Masso, Tla-o-qui-aht’s Natural Resources Manager and director of the Tribal Parks program, during the Nov. 13 annual Tribal Parks Gathering at Tin Wis Resort. “We hope to do good by all of you, and we hope that you’re all proud and staunch advocates of Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks. We hope that you believe in us. We hope that you believe in our rivers and our vision of where we are going.”

Every year, approximately 1.2 million visitors flock to Tofino. B.C., located in the ḥaḥuułi (traditional territory) of the Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation (TFN). With the vision of creating a sustainable tourism model and building strong relationships, TFN Tribal Parks has slowly gained momentum within Tofino’s tight-knit business community to participate in a “potlatch economy”.

In traditional Tla-o-qui-aht society, masčim (citizens) contributed what they could as a tithe to their ḥaw̓ił (chief), who redistributed the wealth. Today, Tribal Parks places an expectation on businesses within their ḥaḥuułi – sign-up to become a Tribal Parks Ally and start collecting a 1 per cent fee from customers.

“The money that is collected here, stays here,” said Masso. “It’s not going to go to Ottawa or Victoria, it’s going to stay here as a legacy to all your grandchildren. We want you all to feel good about that,” he continued.

Speaking the truth is bitter as Masso releases a sigh and talks about the six weeks his Guardians spent monitoring the local rivers for salmon.

“There’s chum, there’s coho, but we didn’t find a single female chinook for our hatchery this year,” he said.

With the new conservancies established in collaboration with Ahousaht First Nation and the Province of B.C. to protect 77,600 hectares of coastal temperate rainforest, Masso says he feels “good that our culture will be intact in accessing monumental cedars for our future.”

But the rivers remain broken from unsustainable logging practices and “the cost of rebuilding these rivers is immense,” Masso says.

Tla-o-qui-aht elder and carver Joe Martin echoed the urgency.

“I really hope that more people will support the Tribal Parks Allies. And I really feel that percentage needs to be increased. What that is, is pittance. I think it could be a little more. If you want to come here, you should support,” said Martin.

Masso said Tla-o-qui-aht forwent a longhouse to invest in the protection of Tofino’s drinking water, which flows from creeks on Meares Island.

“We suffer for tourism. It’s unfathomable that a hotel would not sign up to be an ally when their clients are drinking the water from Meares Island that would have been logged and devastated,” Masso said.

Tla-o-qui-aht’s hope is to build a longhouse in Opitsaht, one of the oldest traditional village sites on Vancouver Island, that is large enough to host upwards of 600 people. They would also like to build an athletic hall with two basketball courts and a maternity ward, so they can “bare children in their homeland.”

“We need this for our culture. It shouldn’t be a wish, it’s a need. I hope to get there in my lifetime,” Masso said.

Maureen Fraser, a longtime Tribal Parks Ally and owner of the Common Loaf Bake Shop, was there in 1984 when the original one-page Tribal Parks Declaration of Meares Island was read.

“It was an electrifying experience,” said Fraser.

She said the moment forever transformed her perspective of the land she’s called home for the past 50 years.

“One of the terms used in the declaration is ‘garden’. We in western culture can understand that a garden is something that you have to work hard in. You have to do a lot and you have to protect it, but mostly it’s a place where you do a lot of work in order to be able to live off the proceeds of that garden. And that’s what’s been happening for millennia. That’s what’s happening still now with Guardians,” said Fraser.

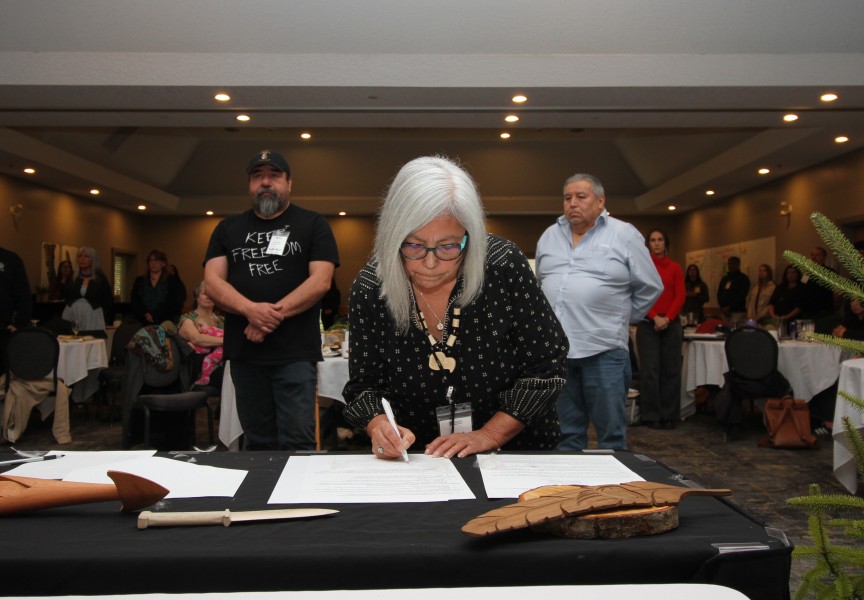

In 2024, 40 years after Tla-o-qui-aht ḥaw̓iih (Hereditary Chiefs) declared Meares Island a Tribal Park, the First Nation created a new Tribal Parks Declaration that asserts four terrestrial Tribal Parks within the ḥaḥuułi: wanačas hiłhuuʔis (Meares Island), ḥiłsyakƛis ʔunaacuł (Tranquil and Tofino Watershed), ʔaʔukmin (Kennedy Lake Watershed) and hiisawista (Esowista).

The new declaration also asserts a fifth Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Park – Deep Ocean, which encompasses the extent of the nation’s offshore fishing and whaling sites.