While he didn’t live long enough to benefit from his win over British Columbia’s organ transplant rules, David Dennis’ victory five years after his death will benefit Indigenous people on waitlists into the future.

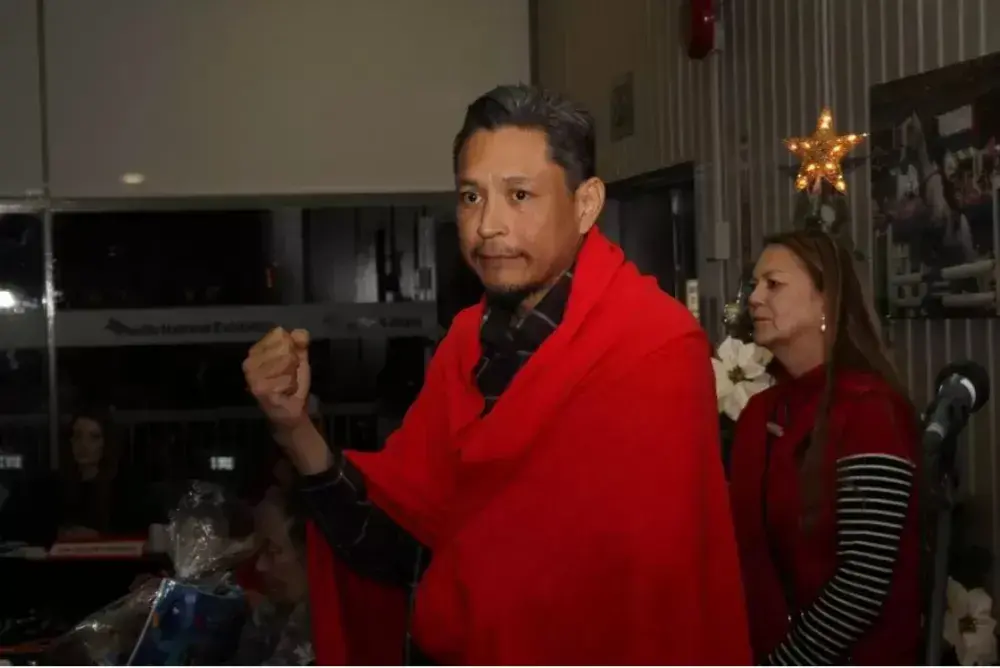

David Dennis, a Huu-ay-aht father of five, was known for his work as a First Nations activist, and he served as Southern Region co-chair at the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council. As a young man, Dennis joined the Native Youth Movement rallying against the B.C. treaty process. He later started up the West Coast Warrior Society to continue fighting for Indigenous title and rights in a more direct, assertive style, according to fellow Warrior, Terry Dorward.

But the West Coast Warrior Society eventually disbanded. Dennis went on to work for and with Indigenous organizations, taking a less confrontational approach in his fight for the rights of his people.

In June of 2019 Dennis was diagnosed with end-stage liver disease. In urgent need of a life-saving liver transplant, Dennis was referred to the BC Transplant, a program of the Provincial Health Services Authority. BC Transplant oversees all aspects of organ donation and transplant across the province and manages the BC Organ Donor Registry.

Following his assessment for transplant suitability Dennis received distressing news. He could not join the waitlist for a transplant because of a policy that required abstinence from alcohol for six months. When he received this news he had quit drinking since his diagnosis two months earlier, but the disease was progressing quickly.

Calling the policy discriminatory, Dennis, with the support of the BC Union of Indian Chiefs and the Frank Paul Society, filed a complaint with BC Human Rights Tribunal.

“The abstinence policy places Mr. Dennis’ health at risk, potentially fatally, by delaying his access to a transplant,” reads the complaint.

The Union of BC Indian Chiefs went on to say that the policy, “is also an affront to his sense of dignity, respect and self worth.”

By September 2019 BC Transplant said that they were changing the abstinence policy based on “new, emerging clinical evidence.” But for David Dennis, the policy change came too late for him, and he knew it.

“They’ve changed their stance, which will benefit ultimately a lot of our kuu’us people because they won’t be faced with the same barriers,” he told Ha-Shilth-Sa in December 2019.

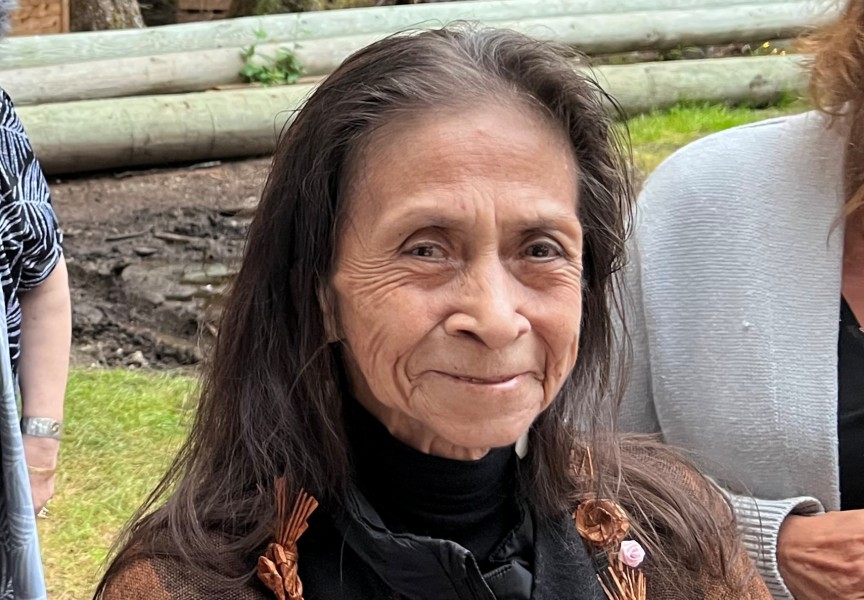

In November 2025 Dennis’ daughter, Somer McCarthy, received a call from her father’s lawyer

“His complaint has now been officially settled,” she said.

McCarthy said the lawyer informed her that the provincial government settled the complaint before it went to the BC Tribunal Hearing, which was set to begin within days.

In a joint statement dated November 20, 2025, the Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs, Vancouver Coastal Health and PHSA confirmed that they had reached an agreement regarding class complaints made through the BC Human Rights Tribunal (BC HRT).

“Under the agreement, UBCIC will withdraw its complaints with the BC HRT and VCH and PHSA will make specific amendments to British Columbia’s liver transplant guidelines,” stated the parties.

Amendments to the guidelines are meant to ensure that if barriers to transplant eligibility and priority for Indigenous patients experiencing liver failure are identified, best efforts will be made to assist patients to mitigate or eliminate those roadblocks.

“This includes supporting Indigenous patients in accessing any needed psychosocial or financial supports throughout the referral, transplant eligibility review, and transplant processes,” reads the joint statement.

“[T]his fight came at huge cost to my father,” wrote McCarthy in an email to Ha-Shilth-Sa. “He filed the complaint while he was given weeks to live, arguing that the abstinence policy was discriminatory and ignored the realities our people face. The impacts of colonization, trauma, intergenerational harm, and the lack of culturally safe healthcare. He stood up even while he was suffering because he knew other Indigenous families would walk this same path behind him.”

She went on to say that shortly after her father’s complaint was filed in 2020, he was placed on the BC Transplant wait list. But his illness rapidly progressed, and Dennis died in hospice on May 29, 2020, at the age of 45.

Through her tears, McCarthy told Ha-Shilth-Sa that it is a relief that this is over. She said she and her siblings are sad but proud.

“Seeing change in policy brings pain and comfort at same time for all of us. My dad should still be here,” she said.

The BC Transplant guidelines include policy changes that came as a result of new information. This includes knowledge that First Nations people have a genetic predisposition to liver diseases like primary biliary cholangitis, which is not caused by alcohol use.

According to the joint statement, guideline amendments were made concerning all patients with primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), auto-immune hepatitis (AIH), or other cholestatic liver diseases who are referred for transplant.

“PBC is an autoimmune disease disproportionately affecting Indigenous people, particularly coastal First Nations people, at approximately eight times the likelihood of non-Indigenous people, and nine out of 10 PBC patients are female,” stated the parties.

“Even though he is no longer here, this settlement confirms what he always knew – the system treated him unfairly and his voice made a difference,” said McCarthy.

But she is proud to say that it was his courage that forced the province to look at the harm these policies caused. This announcement, she said, proves that his life, his fight, created real change.

“As the recipient of a liver transplant myself, I am deeply proud of our joint work to ensure that Indigenous peoples have equitable access to liver transplantation,” said Grand Chief Stewart Phillip, UBCIC president.

“I take comfort because his voice made a difference. Even though he’s not alive, it will protect a lot of people,” said McCarthy.

His voice may even make a difference in the life of McCarthy’s infant daughter. Born earlier this year, McCarthy said her baby is Dennis’ first granddaughter – one that he never got to meet.

The UBCIC acknowledged David Dennis in a statement.

“[He] raised concerns about inequities with a liver transplant policy and fought courageously for fairness and equality in organ transplant rights until his passing in 2020,” said the organization.

“We recognize the historic harms and challenges Indigenous people have confronted and, in many cases, continue to face when accessing health care in B.C.,” said Penny Ballem, interim president and CEO of the Provincial Health Services Authority. “These changes reflect our commitment to reconciliation and our ongoing efforts to create a safe and equitable health care system that serves all people living in British Columbia.”

McCarthy said she and her siblings are proud of the fighter that their father was.

“My late father has helped move this province toward justice,” she said. “Our people will remember him not just as an activist but as a father and a community leader not just in our homelands but also the work he’s done on the Downtown Eastside in Vancouver and across Turtle Island.”

British Columbia is the first province to make this change, but McCarthy expects that this settlement agreement will be far-reaching.

“He was a warrior who never stopped fighting even when he was running out of time,” said McCarthy. “He told my mom, even if he changed one person’s life, that is what mattered to him.”