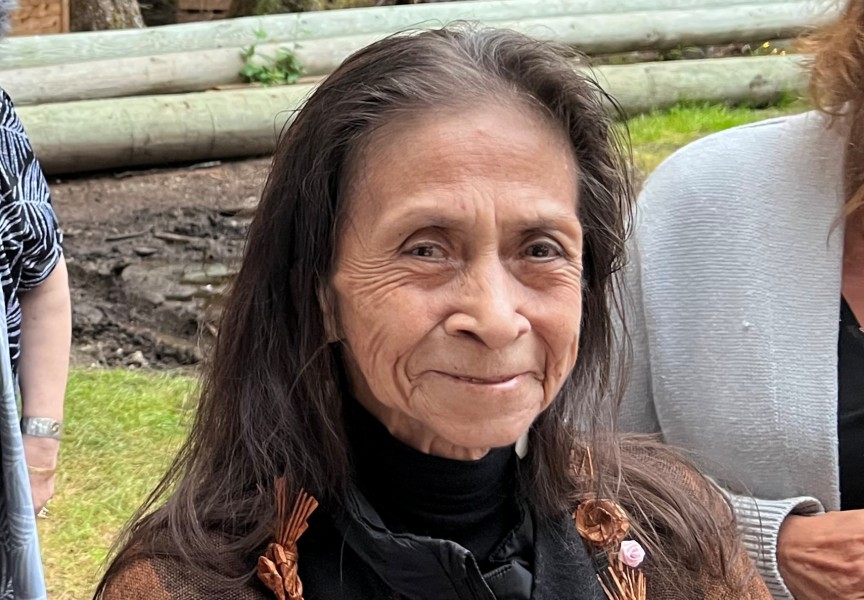

Just over a year ago, the ache in Cheryl Amos’s lower abdomen had become unbearable, leading her to seek emergency treatment at the West Coast General Hospital.

“I was in deep pain, intense pain, and I was throwing up for three days non-stop, so I went to the hospital,” recalled the Tseshaht member.

She was hooked up to a machine intravenously for her dehydration, and given Gravol for nausea, but after she was released her situation had not improved the following day, when she recalls returning with a bladder infection.

“I kept throwing up,” said the 71-year-old. “I went there three consecutive days.”

By the third time she was in the West Coast General’s emergency department, a doctor seemed unconvinced that Amos had a problem requiring medical treatment.

“She says to me, ‘Cheryl, have you been drinking?’,” recounted Amos. “‘No not at all. Not in the least. Besides, you’ve got my blood tests,’ I said to her.”

“She said to me, ‘There’s absolutely nothing wring with you’,” continued Amos. “I just got up and left because she insulted me.”

The elder went home, treating the pain in the bottom left side of her stomach and lower back with hot water bottles. But the agony didn’t subside, and five days later she was back in the hospital, desperately seeking treatment on Oct. 13, 2020. This time painkillers and more Gravol were prescribed, plus liquid potassium to help recover her body from the effects of constant vomiting. But Amos kept throwing up, and continued to seek help in Port Alberni’s hospital, a drawn-out ordeal that has totaled 25 visits to the emergency department over the last year.

Day surgery was finally arranged for Feb. 5 of this year, but the scope failed to locate the source of Amos’s pain. Meanwhile her body had become severely bloated, and 85 pounds had been put onto her frame that normally weighs 135, said Amos.

“I gave a urine specimen and it was the colour of iced tea,” she recalled, noting that the pain was taking its toll on her physically. “My lower back was giving out because of it.”

She long suspected her kidneys were the location of the problem, but as the emergency hospital visits continued, the series of doctors she saw were unable to pinpoint the source of the pain, said Amos.

“It was constant, I couldn’t touch it, I couldn’t wear my waistbands at all. I kept telling them at the hospital it’s right here. I told every single doctor I’ve seen,” she said. “But what is so frustrating is that I couldn’t get them to look into what was really wrong.”

A CT scan on Oct. 6, 2021 also failed to pinpoint the problem, but the agony finally began to ease when Amos left the hospital with a prescription for painkillers and antibiotics for a badly infected kidney.

“By the ninth it eased off,” she said, recalling the first time her condition has been pain-free in 18 months.

Amos has a family doctor, but she hasn’t seen him in over a decade due to discomfort and “very bad incidents,” she said. The COVID-19 pandemic has also limited availability to family doctors, making an immediate appointment to seek answers about her pain an impossibility. Amos has been unsuccessful in securing another general practitioner in Port Alberni, where there is one family doctor for every 700 residents, according to data from the College of Physicians and Surgeons of B.C. and the last Canada census.

According to a provincially commissioned report released by Mary Ellen Turpel-Lafond in February, Amos’s reliance on the emergency department is not unusual among First Nations people in B.C.

“First Nations, on average, are 75 per cent more likely to visit the emergency than anyone else - and the reason for that is that they are not attached to primary care,” said the former judge and provincial child advocate during a Feb. 4 press conference. “Their needs get more acute because they don’t get primary care. And when they go into emergency, it may not be the place to do the referral, to do the communication, to provide the culturally-safe care, because at times emergency departments themselves are in a state of crisis.”

This dynamic has been taxing the provincial system, said Health Minister Adrian Dix when Turpel-Lafond’s report was released.

“The fact that so many people around our province, Indigenous people, encounter the health care system through the emergency room and not through primary care is a challenge to our health care system,” he said.

“Unfortunately, right now these instances are far too familiar, and nothing is happening with reporting,” stressed Mariah Charleson, vice-president of the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council. “We’ve seen a Nuu-chah-nulth member, somebody who was in dire need of medical assistance, and they were banned from the West Coast General Hospital.”

Poor access to a family doctor is particularly concerning among First Nations people over 65, said Turpel-Lafond.

“These elders are not attached to primary care at a rate 89 per cent higher than non-First Nations people in British Columbia – and that, in fact, is quite a staggering finding of this data report,” she commented. “Poor access to primary care may be driving the lower screening rates for treatable cancers.”

Comfort with a physician in an institutional setting could already be a challenge for those who attended residential school or an Indian hospital in their youth, noted Charleson.

“There’s already that distrust, so if you’re thinking of receiving care and you already have these layers and layers of distrust, it’s going to be really difficult to communicate,” she said. “Many of our people will just refuse to go and get help altogether.”

But improvements could be possible through better advocacy to personally help someone navigate through the health care system, something Charleson is pushing for during meetings with First Nations leaders and health officials.

“We want to see 24-7 access to an advocate in the hospital for instances like this,” she said. “We think that can go a long way.”

After more than a year of struggle, Amos has been referred to a kidney specialist in Victoria, thanks to her connecting with the NTC nursing department.

“They were exceptionally helpful, thoughtful,” she said. “I’m wondering why I didn’t turn to them long ago.”

As a kidney problem has become the more likely source of Amos’s pain, she has lost a significant amount of weight by cutting down on salt and controlling her diet.

“I’m not going to go back to the hospital, because I’m sick and tired of it,” she said. “I want other people to speak up because there’s so many other incidents.”

Amos hopes to eventually return to her career of assisting others in long-term care after her health progresses.