Benedict David has always felt an affinity towards the ocean. Born in a “little hole in the wall” cabin on Nootka Island, the surrounding Pacific waters were like his playground.

He spent his childhood on Meares Island, off the coast of Vancouver Island, living in the remote Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation village of Opitsaht.

David has vivid memories of trailing behind his mother through the forest to pick blackberries.

“We were free,” he said.

All of that changed when an Indian agent came to take David away in 1949.

While trapped at Christie Residential School on Meares Island for seven years, the views of the ocean became David’s only reprieve.

He was merely eight years old when the sexual abuse, beatings, and starvation began, and likens the experience to a war.

“I went through hell in school,” he said. “You never ever forget what happened to you in school.”

After “serving” time at residential school, David’s family relocated to the United States, where he completed high school. He was just getting settled into his new life in Yuma, Arizona, before the Vietnam War knocked on his door.

He had two choices – to either enlist or risk being drafted.

If drafted, David said he could be placed in the Air Force or the Army, but if he enlisted, he could return to the ocean by joining the Navy.

“It felt good to be near the water again,” he said.

Having already endured a “war” at residential school through “brutal” beatings and torture, David said he was able to “tolerate” what he saw while serving two tours during the Vietnam War.

In some ways, he said, residential school prepared him for it.

“Vietnam is not a good experience for anybody,” he said.

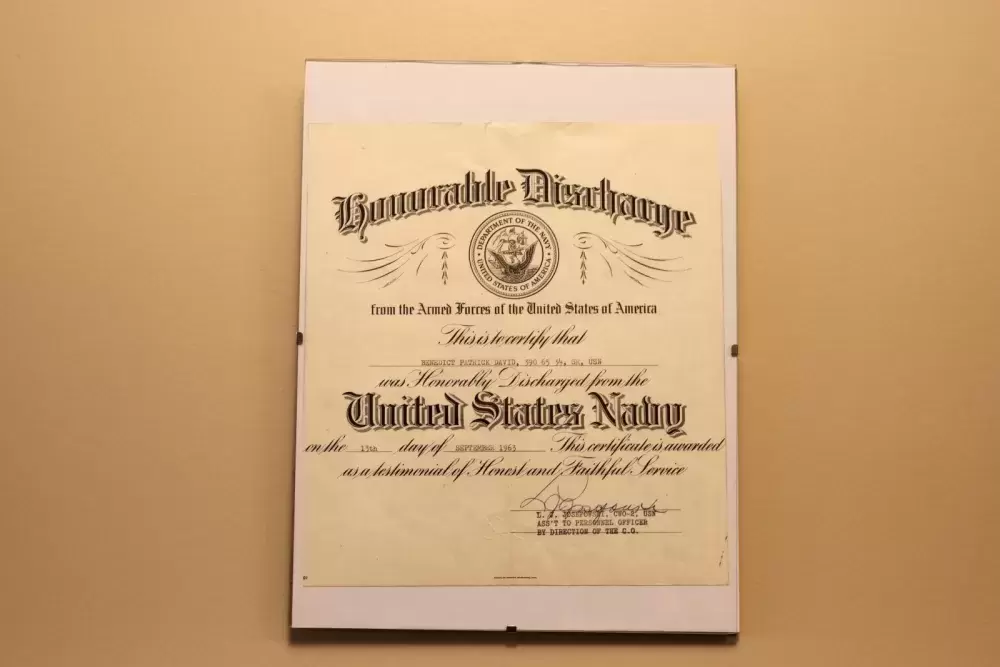

And yet, that period of his life hangs like a badge of honour inside his home at the Tsawaayuus (Rainbow Gardens) assisted living facility in Port Alberni.

The 79-year-old’s collection of veteran hats are lined on his kitchen table. Above them, his United States Navy honourable discharge certificate is centred on the wall.

It’s a period of his life not many people know of, he said.

In part, because he finds it difficult to speak about.

“It was pretty heavy stuff,” he said.

After the Navy, David went on to work as an executive chef for 30 years in Seattle before returning to his homelands with his wife, Grace.

When Remembrance Day rolls around every year, he finds it hard to put his emotions into words.

Serving in the war “was just a part of my life,” he simply said.

“I’m proud of the fact that I was in the armed forces and I served my country,” he said. “That’s not something everybody can say they did.”

His sacrifice meant something.

“We were fighting for a cause,” he said. “For our young people that weren’t yet born – so they would be born into a free country.”