This week a court in Vancouver hears from First Nations affected by residential schools to determine if Canada should proceed with a $2.8-billion settlement to help communities recover from long-standing harms caused by the assimilationist institutions.

The Gottfriedson Band class action litigation is scheduled to be heard in Federal Court Feb. 27 - March 1 to determine if the terms reached between the Government of Canada and the plaintiffs are “fair, reasonable and the best interests of the class as a whole,” according to a website from the legal team behind the lawsuit. The class action is named after Shane Gottfriedson, a former elected chief of the Tk'emlups te Secwépemc First Nation who launched the litigation. It builds upon the Gottfriedson Day Scholars settlement of 2021, which applies to those who attended residential schools but did not live at the institutions.

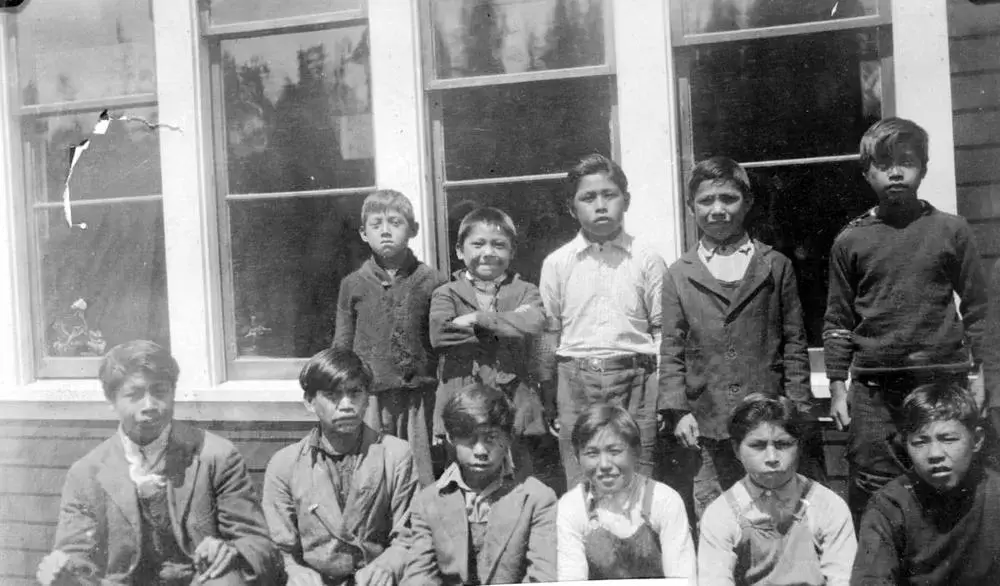

The litigation affects 325 First Nations that were affected by Canada’s residential school system, which forced over 150,000 Indigenous children to enrol in Christian-themed institutions from the 1860s to the 1990s. Seven Nuu-chah-nulth First Nations are included in the class action for how the Christie, Ahousaht and Alberni Indian Residential School affected their communities: Ehattesaht/Chinehkint, Ahousaht, Tla-o-qui-aht, Tseshaht, Hupacasath, Uchucklesaht and Huu-ay-aht.

This litigation differs from the previous individual settlements given to residential school survivors that resulted from depositions collected by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada.

“This lawsuit is not about harms suffered by individual survivors who attended Indian residential schools – instead it is about the collective harm suffered by Indigenous communities as a group as a result of Indian residential schools,” explained the class action’s website.

On Jan. 21 Canada’s Ministry of Crown-Indigenous Relations announced an agreement with the 325 First Nations tied to the litigation. If approved in court, the settlement would entail the government setting up $2.8 billion in a not-for-profit trust fund “independent of the government,” according to the federal department.

The fund would be managed by a board of nine Indigenous directors elected to represent the plaintiffs, with the dispersal of funds guided by four pillars aimed to revitalize First Nations communities beyond the aftermath of the residential school system. These fundamentals include the revival and protection of Indigenous languages and cultures, the preservation and promotion of ancestral heritage, as well as supporting the wellness of the First Nations’ community members. An initial amount of $200,000 would be available to each First Nation to develop a proposal that follows the four pillars.

“These proposals will be reviewed and used to support the disbursement of the Initial Kick-Start Funds, totalling $325 million,” stated the government’s announcement of the settlement agreement.

The Indigenous communities also would receive a share of the settlement fund’s annual investment income, to be dispersed with consideration given to population size.

Now the Federal Court is tasked to decide if Canada should follow through with this plan. On the first day of court proceedings in Vancouver, Elected Chief Michael Starr of the Star Blanket Cree Nation spoke about how his community continues to be affected by the legacy of the Lebret Indian Residential School, which operated in the First Nation’s territory in Saskatchewan until 1998. The Star Blanket Cree Nation has just one fluent speaker left, he said.

“The loss of language, the loss of culture, the loss of identity, those have impacted us,” said Starr in the Vancouver court room. “I should be here talking in my natural language. I’ve lost it.”

Just as the Tseshaht First Nation are currently engaged in determining how many children died while attending the residential school on its territory by the Somass River, the Star Blanket community conducted ground penetrating radar on the former Lebret site in 2022. Besides numerous radar impressions that indicate possible burials, during the search a jawbone was found, which went to the Saskatchewan Coroners Service for testing. The remains are believed to be approximately 125 years old, belonging to a child aged 4 to 6.

“Before, we never saw that evidence,” said Starr. “If you want evidence, we have that evidence there.”

“We believe that all survivors deserve justice and the compensation to which they are owed,” said Marc Miller, minister of Crown-Indigenous Relations, in a statement. “As we finalize this settlement, we are remined of the importance of collaborative dialogue and partnership in resolving historic grievances outside of the court system.”

“If you approve this, it will be helpful for us to impact our jurisdictional perspective the way we want to do things,” said Starr, who believes that the residential school broke a right-to-education condition of Treaty 4, which was signed by his nation in 1874. “We feel, in a lot of our nations, that it was a breach of treaty, the Indian residential school system, the genocidal residential school policy. But we have endured it, and we are resilient to our past.”