On Monday the Nuchatlaht are back in court, this time to appeal a ruling from last year in hope of proving historical ownership over the inland areas of its territory.

The small Vancouver Island First Nation has four days to appear before the B.C. Court of Appeal, with a trial scheduled in Vancouver Oct. 20-23. This appearance marks the latest chapter in the Nuchatlaht’s quest to gain Aboriginal title over 201 square kilometres of land encompassing the northern part of Nootka Island – a court battle that began over eight and a half years ago when the late Tyee Ha’wilth Walter Michael filed a claim to the B.C. Supreme Court in January 2017.

This current appearance seeks to build on Justice Elliott Myers’ ruling from April 2024. After nearly 60 days in court the judge determined that the Nuchatlaht are the rightful owners of a portion of the area they claimed, amounting to 12 square kilometres – most of which is on a strip along Nootka Island’s northwest coast that doesn’t extend more than a kilometre inland.

During court proceedings the Nuchatlaht’s legal team argued that the claim area’s entire watershed should be recognized due to the traditional use of the whole area, but Myers remain unconvinced. With a few small exceptions that he added, the judge’s definition of the Nuchatlaht’s title land generally aligned with the provincial government’s argument to the court.

Myers determined that the Nuchatlaht treated the interior of the rugged region differently than coastal areas where evidence of settlement can be found.

“With respect to the interior, there is almost no evidence of use by the Nuchatlaht,” wrote Myers, who was unconvinced that the nation’s ancestors left evidence of occupation above an elevation of 100 metres. “Confining the boundary to the 100-metre contour reflects the distinction between the coastal and interior areas.”

During the past B.C. Supreme Court trial, a major part of the Nuchatlaht’s argument was the hundreds of trees in the area that were partially harvested by the First Nation’s ancestors. Archaeologist Jacob Earnshaw identified 8,386 of these culturally modified trees (CMTs) in the claim area, but in his ruling Myers noted that these sites have an average distance of 845 metres from the shore, pointing to the heavy reliance that Nuu-chah-nulth people historically had on the ocean.

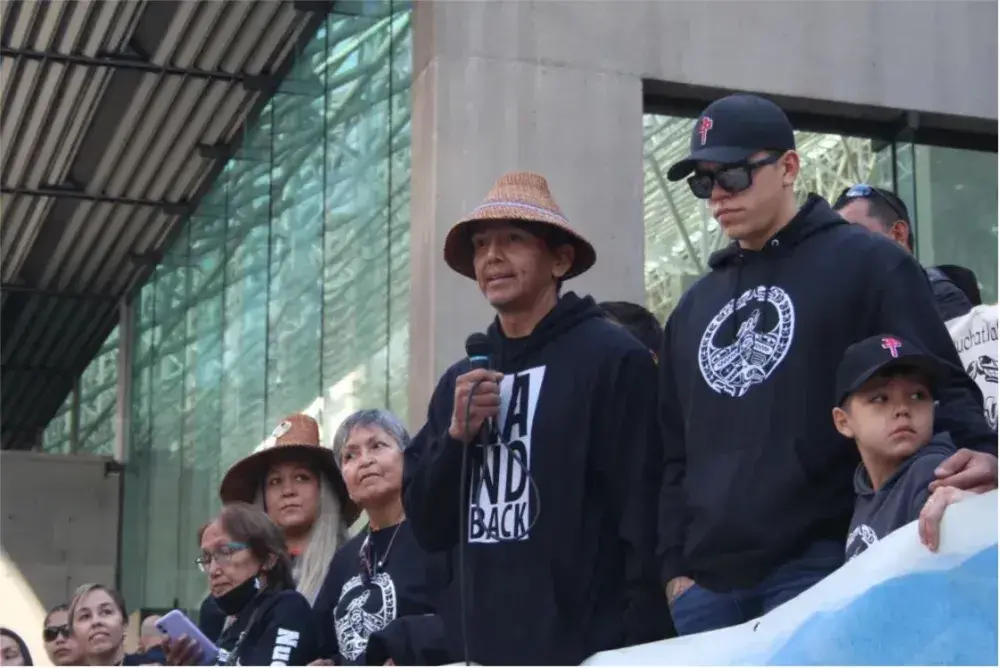

In a statement from the First Nation this month, Tyee Ha’wilth Jordan Michael said that evidence of past occupation can be found throughout the claim area.

“I’ve hiked through our forests. There’s signs of our people everywhere. Everywhere you look you find CMTs,” said the hereditary chief. “This past summer we found carvings on our title lands.”

With the appeal the Nuchatlaht are bringing several other First Nations into the case to present evidence as intervenors, including the Dzawada’cnuxw, Tseshaht, shishalh and Cowichan, as well as Nuchatlaht’s neighbours to the south and north, the Mowachaht/Muchalaht and Ehattesaht.

The court’s decision hinges on proving a continued, historical occupation and use of the claim area since 1846, the year that the British Crown asserted sovereignty over the region. The rest of the area being contested in court is Crown land, with a harvesting tenure held by Western Forst Products. Logging has ceased as the court case progressed.

“Hopefully they’ll look at our history,” said Nuchatlaht Councillor Archie Little as he awaited the court appeal.

Little spent his early childhood in the village of Nuchatlitz, which is overseen by mountains not included in Myers 2024 ruling. In 1988 the First Nation moved its main reserve from this village site to the coast of Vancouver Island.

“We only have 20 per cent of our trees left,” said Little, who cites thousands of years of sustainable forest management from his ancestors. “All we want is to do better, to show that ownership and that respect.”

With just six per cent of the claim area recognized so far, Chief Jordan Michael has called the past B.C. Supreme Court ruling “a partial victory”. Under Canadian law, the 2024 ruling gives Nuchatlaht ownership over expanded sections of its territory beyond the coastal patches of Indian Reserve land. This includes Owossitsa creek, a sacred sockeye-bearing stream that only the First Nation’s Tyee can access for fish.

“We’ve opened it up so our people can see the area. We’ve built a road where we can drive it, tourists can go there,” said Little, noting the Nuchatlaht plan to put up signs with rules encouraging visitors to respect the Ḥahahuułi. “There’s evidence of two longhouses that you can see as you drive on that road.”

The newly recognized title land also includes Nuchatlitz Provincial Park, which Little says was previously established without the First Nation’s consent.

“They made a provincial park in that area, and then we were given that land in the title,” he said. “We’ve got some cabins that non-Aboriginals built. Well, they’re ours now.”

As the Nuchatlaht look to the future use of its land, Little said they are not against harvesting, but it needs to be done differently than under the province’s forestry tenure to ensure that enough will be left for future generations. The title case was originally launched when it became clear that Western Forests Products’ views did not align with what Nuchatlaht wanted for the territory, explained Little.

“We made some demands of Western, and they said a flat no right away,” recalled Little, who sat in these talks alongside the former Tyee Walter Michael. “They said, ‘because our bosses are in New York, the stockholders’. I said, ‘No, your boss is sitting right here. He owns it’.”