Earlier this week Parks Canada officials announced that dogs are now banned from being on a part of Wickaninnish Beach, located on Nuu-chah-nulth territory south of Tofino.

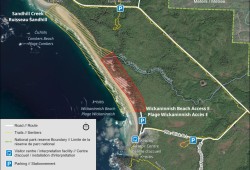

The ban, which came into effect on Feb. 11, prohibits dogs from being on the section of the beach from Beach Access E to Sandhill Creek. This area is in Ucluelet First Nation territory.

An incident just one day later led to an expansion of the ban. It was announced on Feb. 13 via the Pacific Rim National Park Reserve’s Facebook page that two wolves had attacked a dog on the Willowbrae Trail the day before.

This 2.8-kilometre trail begins south of the Ucluelet/Tofino junction.

As a result of this latest attack, dogs are now also prohibited on the stretch from Willowbrae Trail to Green Point Rocks.

Parks Canada officials said the Wickaninnish Beach ban was necessary because there has been an increase of interactions with wolves and humans, especially those who are with dogs.

An increase in aggressive behaviour from wolves has been noticed because they consider dogs as a competitor or prey.

Liam McNeil, the acting resource conservation manager for the Pacific Rim National Park Reserve, felt now was the appropriate time for Parks Canada to implement the ban.

“Human and wildlife safety is of the utmost importance to Parks Canada,” he said. “And we take proactive action to promote safe co-existence between people and wildlife.”

The ban is a follow-up to a wolf warning Parks Canada had issued this past September, recommending that visitors leave their dogs at home because of an increase in the number of wolves and wolf encounters in the area.

McNeil felt it was vital to ramp up action from a warning to the ban of dogs in the area.

“This restricted activity order responds to a marked rise in human/wolf interactions in the Long Beach Unit since 2024, influenced in part by an increase in the number of wolves in the area,” he said. “Multiple recent incidents have involved wolves closely approaching or following dogs, and Parks Canada has implemented management actions to reduce these interactions.”

The latest ban is also a stepped-up increase in past proactive safety measures, including closures in the Wickaninnish Dunes and the former Gold Mine Trail.

McNeil said there were more than 40 reported wolf encounters in 2025 in the region. The majority of those occurred in the Long Beach Unit of the Pacific Rim National Park Reserve.

Other dog regulations have also been in existence in the Long Beach area.

For example, unless they are certified service pets, dogs are not permitted on the West Coast Trail or the Broken Group Islands at any time.

There is also a seasonal dog closure, from April 1 through Oct. 1, on Combers Beach. This particular closure is in place to protect migratory shorebirds during vital feeding and resting periods.

Disregarding leash laws, area closures or dog prohibited areas can result in charges, including a maximum fine of $25,000.

McNeil confirmed some individuals have indeed been charged under the Canada National Parks Act for violations related to dog regulations.

“We all have a shared responsibility to keep pets on leash and obey warnings and restrictions,” he said. “Where dogs are allowed, keeping pets on leash and under physical control at all times is the law. And it protects both your animal and the wildlife that live here.”

Parks Canada reps suggest those who are planning to visit area’s parks should always seek out existing advisories and closures before they venture out.

McNeil added not having dogs on a leash can lead to problems.

“Off‑leash dogs can trigger defensive or aggressive behaviour from wildlife or unintentionally harm smaller animals,” he said. “Compliance is something we are always working toward through education and enforcement.”

Parks Canada officials added the latest ban will remain in place until further notice. Also, wolf sightings and interactions will be closely monitored to get an indication how long the ban should last.

Besides having a valuable cultural significance for First Nations, wolves are also considered a vital part of the ecosystem.

Human behaviour can have a huge influence on wolf movements.

“Wolves in Pacific Rim National Park Reserve are highly aware of people, even when they appear calm or distant,” McNeil said. “Parks Canada monitors wolf activity using remote cameras and other research tools to better understand movement patterns and behaviour while minimizing disturbance.”

While humans might be rather curious upon spotting a wolf, McNeil suggests it is not ideal to follow them.

“Seeing a wolf in its natural habitat can feel like a once-in-a-lifetime experience,” he said. “But people should never try to watch, follow or observe wolves - even from afar. Repeated exposure to people can change wolf behaviour, leading to habituation or food conditioning. These outcomes significantly increase the risk of conflict.”

Several other Nuu-chah-nulth First Nations have territories in the Pacific Rim National Park Reserve.

They include Ditidaht, Hupačasath, Huu-ay-aht, Tseshaht, Toquaht, Tla-o-qui-aht and Uchucklesaht.

Parks Canada undertook a six-year project, titled Wild About Wolves, which explores how humans can co-exist with wolves. The Wild About Wolves website can be viewed here.