A policy that guides how much salmon can be caught by various groups is due for revisions, and while the sports sector warns that “Your right to fish is in danger”, Nuu-chah-nulth organizations are pushing for more balanced allocations that reflect court-affirmed rights.

In late January the public input period closed for the next phase in how Fisheries and Oceans Canada will update its Salmon Allocation Policy. Next in the process is for various stakeholders to meet this winter to finalize recommendations to the minister of Fisheries and Oceans, Joanne Thompson. Involved in these discussions are representatives from DFO, commercial fleets, the sports fishing sector and the First Nations that call the waters under examination their ancestral home.

Since it was introduced in 1999 the Salmon Allocation Policy has served as the guide for the DFO to determine harvest limits amongst commercial, recreational and First Nations fisheries. But since that time conservation concerns have intensified for certain West Coast stocks, while courts have determined that the policy wasn’t fair to Nuu-chah-nulth nations in the first place. In 2018 the B.C. Supreme Court ruled that the policy had unjustifiably given the sports sector priority to fish chinook and coho over the rights of five Nuu-chah-nulth nations to catch and sell salmon from their respective territories.

After the court upheld the commercial harvest rights of the Ahousaht, Ehattesaht/Chinehkint, Hesquiaht, Tla-o-qui-aht and Mowachaht/Muchalaht First Nations, Canada’s fisheries minister at the time directed staff to review the policy behind the catch limits. After years of meetings, DFO released a discussion paper in 2025, noting that First Nations recommend removing the language “common property resource” from the policy, “noting concerns that it is a colonial concept which has been harmful to First Nations, salmon, and ocean ecosystems.”

But the Sports Fishing Advisory Board wants the “common property” clause to remain, stressing that “salmon’s status as a common property resource remains an overarching principle informing allocation,” summarizes the DFO discussion paper. “Further, they indicate that the public right to fish continues to hold legal significance as a right of all Canadians.”

“Your right to fish is in danger,” warns a campaign launched by the B.C. Wildlife Federation.

The organization, which advocates for hunters, anglers and outdoor recreationalists in the province, states that “while Aboriginal and treaty rights take priority, the public right to fish should not be infringed or extinguished by Aboriginal rights.”

“The public right to fish is cherished by Canadians,” stated BCWF Executive Director Jesse Zeman. “I cannot conceive of a world where I can’t take my children out to fish, let alone their children. A right lost will be lost forever.”

The Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council sees this rhetoric as inflammatory that could threaten public safety.

“Nobody is being shut out of the water,” stated a press release from the NTC. “Nuu-chah-nulth nations are seeking removal of outdated policy language that treats all user groups as if they hold equal rights, despite constitutional and court-affirmed Indigenous priority.”

“First Nations have lived here for thousands of years. Fishing for salmon has always been a significant food source, a part of our economy and a part of who we are as people,” states the Ha’oom Fisheries Society, which advocates for the rights of the five nations. “DFO must make room for us – right the wrong and rebalance the fishery. Our families want a viable, sustainable fishing economy and the revival of coastal communities that supported it.”

With a complex system of coastal economies at stake, the DFO is now tasked with how to fairly revise its approach to managing harvest limits on a resource that has faced increasing threats over the last generation. Seventy per cent of salmon stocks are below their long-term average abundance, according to the Pacific Salmon Foundation.

In 2018, the year that the federal department’s staff were first tasked to look into changing the Pacific Salmon Policy, the recreational fishery on the west coast of Vancouver Island was given a larger chinook allocation than any other group. Back then a total allowable catch of 88,300 was set for the region, of which 50,000 chinook were allocated to the sports fishery. Commercial fleets got 20,132, Maa-nulth treaty nations had 3,447, the five nations’ rights-based fishery of T’aaq-wiihak were allotted 9,721 and 5,000 chinook were set for First Nations food, social and ceremonial purposes.

Recreational catches declined during the COVID-19 pandemic, but by 2024 the sport chinook harvest had rebounded to 47,656, out of a total of 96,128 caught off the west coast of Vancouver Island, according to the most recent numbers published by the Pacific Salmon Commission. Meanwhile 24,154 chinook were caught by the commercial troll fleets in 2024, 3,545 went to Maa-nulth, 3,545 were caught for First Nations food, social and ceremonial and 17,267 were harvested by the five nations’ rights-based fishery.

The Sports Fishing Advisory Board argues that this shouldn’t change, as the recreational sector “provides the highest level of economic, social and cultural benefits” to the public.

“It is clear that the recreational fishery represents the most effective use of Canada’s salmon resource as compared with the commercial salmon fishery,” stated the advisory board, citing thousands of jobs and over a billion in revenue each year. “The recreational fishery produces $693.31 of GDP per salmon caught as compared with the commercial fishery which produces $7.59 of GDP per salmon caught.”

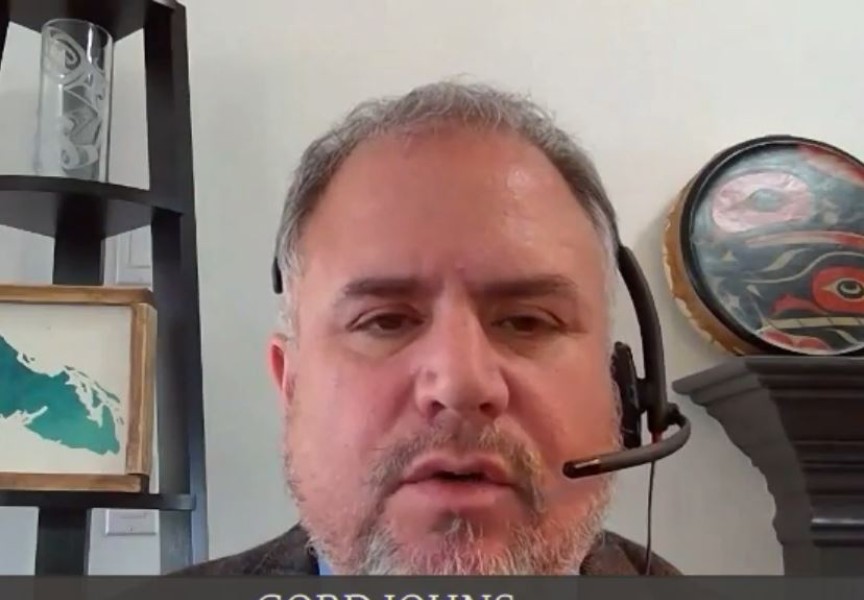

But this isn’t the full story for coastal communities, says Gord Johns, NDP Member of Parliament for Courtenay-Alberni.

“In places like Ucluelet, once one of the largest salmon landing ports in British Columbia, there is now just a single independent salmon troller left,” wrote Johns in a letter to constituents. “Federal allocation choices, including recreational priority and the failure to recognize rights-based Indigenous commercial fisheries, hollowed out small-boat fleets, closed processing plants and stripped economic stability from entire towns.”

Johns also noted that while the concerns of recreational fishers about access and economic impacts “are real and deserve to be heard,” these interests “cannot override court decisions, constitutional obligations, or the survival of the salmon itself.”

“Our nations have relied on salmon for thousands of years, and our rights and responsibilities to these waters are not up for debate,” said NTC President Cloy-e-iis, Judith Sayers. “Canada must bring policy in line with the law and protect salmon for all who depend on them.”